Threads — On Seeing Wide

Why panorama photography gives us a truer view

Besides the wooden camera and my Leica, I’m using my Widelux and Hasselblad XPan, both of which open up a different, panoramic way of seeing. These two cameras were built for one purpose: to see wider than the human eye. Panorama photography has slowly taken over my way of looking, because it does something fascinating. It shows the world almost as we actually experience it… and yet more.

The Mind’s Panoramas

When we look around, our field of view is roughly 160 degrees. We perceive the whole scene, but only a small part of it is perfectly sharp. Our eyes register fragments; our brain quietly fills in the rest. We think we are seeing “everything,” but in truth we only see what is in focus, and our mind constructs the rest into a seamless whole.

A panorama camera works differently.

It makes sharp what the eye registers only partially. It stitches together what normally sits at the edges of our attention, those peripheral impressions we don’t consciously process but that shape the feeling of being somewhere.

A Wider Truth

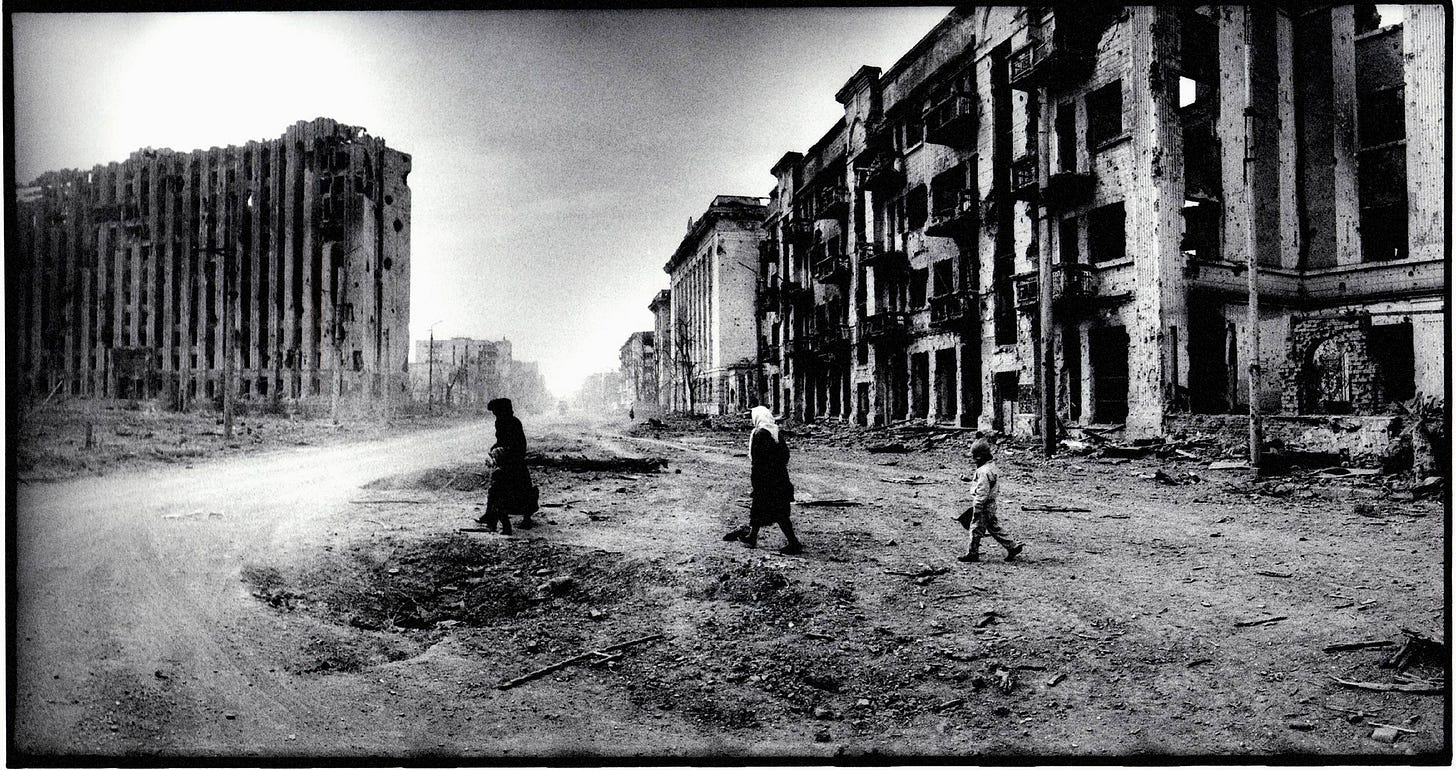

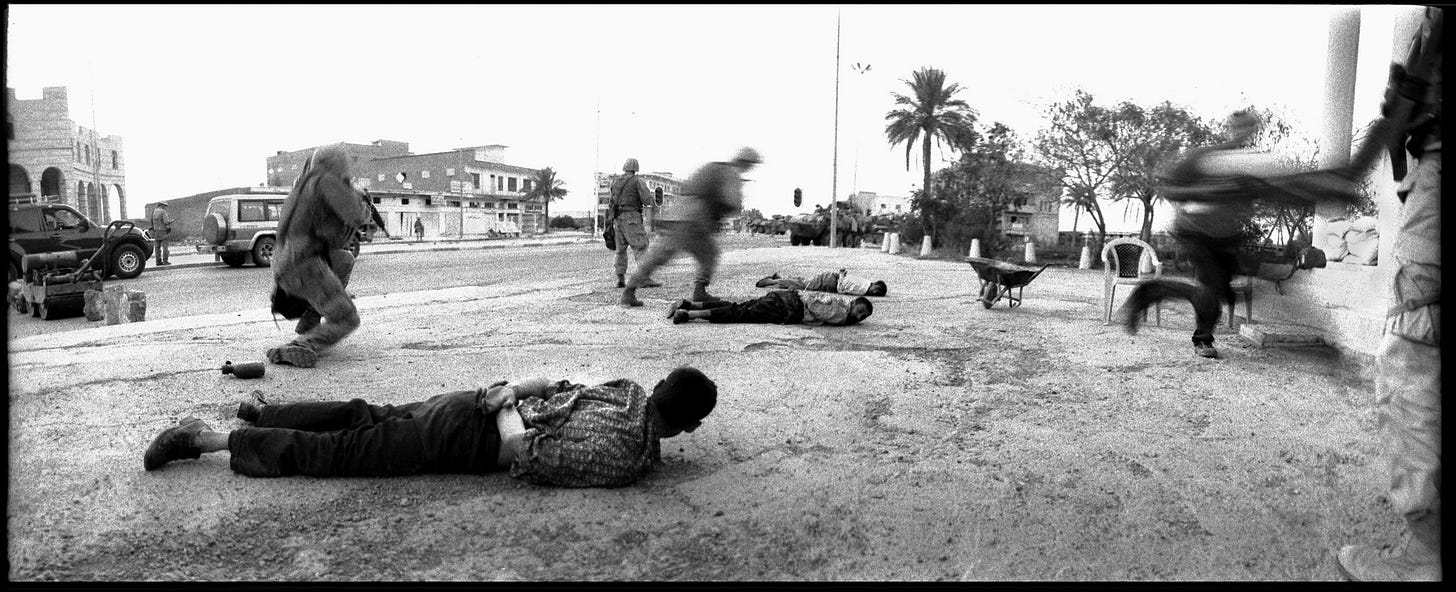

That is why panorama images can feel strangely cinematic, or even truer than traditional photographs. They allow multiple elements to coexist naturally within one frame: contrasts, tensions, unexpected relationships. Things that would require several separate images suddenly live together in a single sweep of space.

In that sense, panorama photography becomes a kind of expanded seeing. It captures the full “thought” of a place rather than just the fragment our eyes choose to focus on.

For me, that makes panorama an intriguing way to photograph the world, especially in places of conflict. From Bangladesh to Irak, from Ukraine to Chechnya. It allows contradictions to exist side by side. It lets silence and chaos share the same plane. It gives the environment its full voice.

My next book will be a panorama book. I know a big statement. But I am quite convinced.

It feels like the natural continuation of the work I’m doing now: looking wider, listening better, noticing what usually stays just outside the frame.

For anyone curious to see more about the power and possibilities of panoramic storytelling, I share these three interesting photographers:

Josef Koudelka — The Holy Land

Perhaps the most influential panoramic photographer working in conflict landscapes. Koudelka uses the wide format to reveal fractures (political, architectural, emotional) all held in one sweeping frame.

🔗 magnumphotos.com/theory-and-practice/koudelka-shooting-holy-land-israel-palestine-documentary-conflict/

Jens Olof Lasthein — Moments in between

Panoramas that feel intimate rather than wide.

🔗 lasthein.se/books-moments

Pieter Ten Hoopen — Stockholm

Poetic panoramas of urban life, where space becomes emotion. His work shows how the wide frame can hold silence, tension, and movement all at once.

🔗 pietertenhoopen.com/photo-stockholm.html

If ever there was a case for panoramic storytelling, it is these photos from Ukraine

Hi Craig, great meeting, see you again.

greetz Eddy